VAAlHAAlla - A Deeper Dive On Fastball Analytics

A deeper dive into emerging pitching analytics that further help explain why certain fastballs play better than others

Recently in July, I wrote about fastball shape, and more specifically Induced Vertical Break (IVB). Since then, I’ve been further looking into the metrics of Vertical Approach Angle (VAA), and Horizontal Approach Angle (HAA). A lot of the intrigue stemmed from stumbling on an article Fangraphs writer Alex Chamberlain wrote in February of 2022, and then looking over his pitching leaderboard (Specs tab) he has generated. Wanting to understand more about it, I reached out to Alex to help dissect his leaderboard. Yahoo writer Zach Crizer also wrote an article back in April that does well to break down some key points.

Anthony Murphy initiates Bucs On Deck’s discussion of VAA and HAA in his Brandan Bidois article, and we want to bring you along in our journey of learning.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll mainly be focusing on VAA, as Alex Chamberlain himself noted to me that he hasn’t “gotten a firm grasp on what HAAs excel.”

VAA, in short, is a measurement of how flat or steep a pitch is, and this will help determine where a fastball is best utilized. In general as Alex put it, the ultra-flat four-seam fastballs will generate swings and misses at the top of the zone, while also generating more called strikes at the bottom of the zone, because they don’t fall as much as perceived by the hitter. Whereas a steep sinker will operate in the opposite fashion, by generating more called strikes at the top of the zone, and more swings and misses at the bottom due to sinking further than perceived. Also including that a flat four-seam at the top of the zone will generate more pop-ups than usual from hitters getting under the ball, whereas a steep sinker will generate more ground balls.

One reason why VAA is important itself as opposed to focusing solely on IVB, is VAA takes into extension and release height. Where “the flattest fastballs tend to come from sidearm-ish slots with roughly 15-16 IVB, and then high-slot guys with 19-20 IVB.”

VAA is going to be measured in degrees, with a pitcher wanting their four-seam fastball to generate a VAA of -4.0 degrees or higher (closer to 0) for the best “rise”, where -6.0 degrees is considered steep (Joe Musgrove). For sinkers, -7.0 degrees or lower are the ones with the best sink.

Does velocity matter? Sure, but you can also be Joe Ryan of the Minnesota Twins who has a 28.3.% Whiff rate on his FF, even with “less than ideal” average velocity on his fastball of 92.4 MPH. The key, as mentioned in the Crizer article linked above, being that Ryan has a VAA of -3.9 degrees with a VAA AA (VAA Against Average) of +0.67 degrees. Where essentially, a pitcher wants a VAA AA deviation to be further away from 0.00, or average.

Does command matter? Obviously, but similar to velocity, a pitcher is able to miss more bats with better stuff. With also the understanding that throwing middle-middle is never good for anything (we’ll get to this).

This is also why Jacob deGrom is such a unicorn, because he pairs elite command, with elite velocity (98.7 MPH), with elite VAA (-4.0 degrees).

So, where does this leave us with the Pittsburgh Pirates pitchers? Mostly, from the MLB starters standpoint, not very promising. If we were to look Stuff+ on Fangraphs, we would see one personal narrative that I’ve been developing myself is their ability to identify, acquire, and develop pitchers with quality sliders. Unfortunately, and as is a main focal point of this article as well, they’re not identifying, acquiring, and developing pitchers with command of their pitches. An important tool for when a pitcher’s stuff is bordering on average. Also makes their recent draft haul a head scratcher.

I think we could all agree that David Bednar has a pretty good FF. Averages 96.6 MPH, an IVB of 17.7 inches, and VAA of -4.1 degrees. If we look at Carmen Mlodzinski, we can see how arm slot and release point as mentioned above can deviate VAA even as IVB drops. Mlodzinski himself has FF with a VAA of -4.1 degrees, while averaging 95.8 MPH, with IVB of 12.3 inches. The kicker is his Vertical Release point is 5.1 vs. Bednar’s of 5.9.

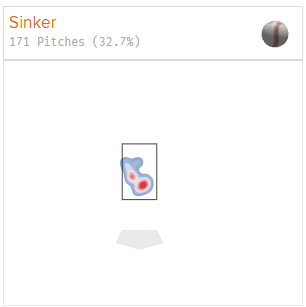

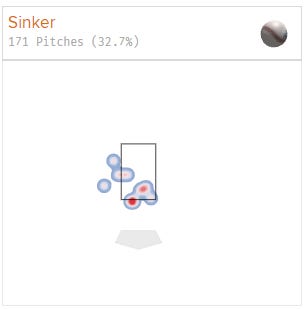

A starter that does stand out to me though is Quinn Priester and his sinker. He doesn’t have a very large deviation (-0.46 VAA AA), but it has a VAA of -6.7 degrees. The four-seam across the board isn’t a very strong pitch. It’s dead zone for a high-slot guy (14.3 IVB and -5.3 VAA), Stuff+ doesn’t like it at all (75 Stuff+ with 100 being average), and the command is all over the place. Commanding his sinker though could be Priester’s key moving forward though. If you look at his heat map on Savant of his pitches, it also hasn’t been pretty from a command standpoint.

This is the map of all 171 Sinkers

This is the map of Base Hits

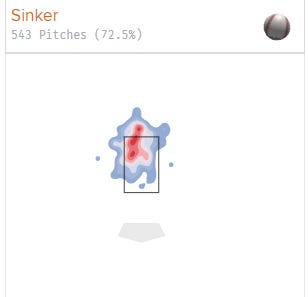

Lastly is the map of Swings and Misses, which shows exactly where you’d expect from a steep sinker

Then for comparison, here is the Swings and Misses chart from Josh Hader, who has a flat sinker, from a low-arm slot. Again, exactly where you’d expect

In conclusion, this is mostly a kick-off article that begins our dive into the underworld of pitching analytics, with more math than even I want in my brain. I considered myself a nerd, but this is more nerd piggybacking. In the following weeks, Anthony and myself will begin looking further into these numbers, especially now since Corey Shrader shared a previously unknown data table from Prospects Live.

Jeff: Third reading and I am still confused, but that's no big thing because my era was "see ball, hit ball"! There will always be new approaches to pitching more efficiently, just as I am sure it will not take very long for hitters to catch up. Technology is a wonderful gift!

Have you watched the movie "Fastball?" It is a great documentary that explains fastball dynamics and examines fastballs throughout history. One thing that the movie points out is the optical illusion that velocity combined with high spin can produce. A high velocity (95+ mph) with good spin that produces lift (like air under the wings of an airplane) appears to hitters to rise and they even say things like, "his fastball just jumps over your bat." Of course, the ball does not rise; it just drops less than one would expect. The illusion is created because at velocities above 95 MPH, the eye cannot track the ball and so jumps from one point to the next where the hitter expects the ball to be. While the eyes are jumping, the brain fills in these jumps in perception with the expected route of the ball, and the brain expects the ball to fall more than it does. This is what creates the optical illusion and strikeouts or swinging under the ball. When the ball arrives, the hitter expects it to be below where it actually is. Velocity is important here though as even fractions of seconds allow for the brain to assimilate more information from the eyes and better track the path of the ball.